Sacrifices for a better world begin at home

Sacrifices for a better world begin at home

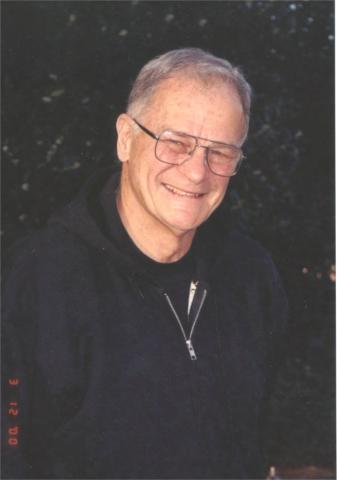

NEXT VALENTINE'S Day, when Charlie Liteky turns 70, it won't be with his wife of 17 years in their home in San Francisco.

Instead, the former Roman Catholic priest, Vietnam veteran and U.S. Medal of Honor winner will have to choose celebratory company from among the 200 inmates he'll be living with in the minimum-security camp at Lompoc Federal Prison.

Liteky's sentence is one year, starting July 31. His crime: Two misdemeanor counts of trespassing during a protest march on the U.S. Army base at Fort Benning, Ga.

Liteky (pronounced "LIT-key") was bearing a fake coffin and headed for the School of the Americas inside Fort Benning when he was arrested last November and again in December.

A controversial training center for what the federal government now calls "counterrevolutionary" education, the SOA was founded in Panama in 1946 and moved to Columbus, Ga., in 1984. It was created by the United States to fight communism in Latin America. Along the way, though, it became the alma mater of hundreds of dictators, thugs, assassins, torturers and military "strongmen" like former Panamanian Gen. Manuel Noriega.

The late Roberto D'Aubuisson was another grad; he is generally credited with planning the 1980 assassination of El Salvador's archbishop, Oscar Romero.

Thanks in large part to the efforts of the Rev. Roy Bourgeois, a Maryknoll priest, and people like the Litekys, the SOA has become ground zero for a massive protest movement against U.S. social, political and economic policies in Latin America.

In November, when Charlie picked up the first of his two trespassing arrests, more than 12,000 women, men and children were in line behind him. Only 10 of them are going to prison.

Among the 10 are two retired ministers (Lutheran and Methodist), a Quaker, a Korean War vet and Sister Megan Rice, a 70-year-old Baltimore nun who served for 34 years as a missionary in Nigeria and Ghana.

"Sister Megan got six months the last time, and six months this time - the maximum," said Liteky. "She's still in jail in Columbus, waiting transfer to a facility near her home. She said the hardest part of being in prison has nothing to do with her - it's witnessing the conditions of the other women inmates."

Charlie Liteky also got the maximum sentence: two six-month terms to be served consecutively, not concurrently.

To those of us outside the world of nonviolent civil disobedience, people like Megan Rice, Roy Bourgeois and Charlie Liteky can seem a little nuts. Crisscrossing the country, getting themselves arrested or fasting to within a few days of death, they threaten their health, comfort, economic stability and, sometimes - as the Litekys have learned - their closest personal relationships.

"On the one hand, I'm out here doing something I think is important, something I believe is bigger than me and my life," said Charlie. "On the other hand, there's this thing called love. And this person I love, who loves me, is suffering because of me. My pain is her pain, hers is mine."

It is no wonder that many of the most committed social justice activists are or were priests, nuns and ministers - people who once answered an ethereal call to service with vows of poverty, obedience and (for some) celibacy.

They deeply believe that sacrifice and personal suffering can bear rich fruit for the oppressed and marginalized. Like Mahatma Gandhi, there are many causes for which they might die, but none for which they'll kill.

Back in 1966, when Charlie Liteky, the priest, volunteered to be an Army chaplain in Vietnam, the notion of no-exceptions nonviolence was missing from his personal radar screen. The son of a career Navy noncommissioned officer, Liteky was comfortable with the military; he trusted its ways.

"I cannot believe the attitudes I had in '66, the things I believed," he said. "I'd been taught about the evils of communism and the just-war theory. I had no problems with us being in Vietnam. I thought I was doing God's work."

To hear the survivors of a Dec. 6, 1967, firefight in Bien Hoa province tell it, Father Angelo (Liteky's ordination name) DID seem to be working for a higher power. Crawling repeatedly through machine gun fire, he dragged 23 wounded soldiers from his battalion to safety in a medical helicopter landing area.

Eleven months later, President Lyndon B. Johnson presented Liteky with this country's top award for heroism in combat, the Medal of Honor.

In July 1986, in protest of U.S. aid to the contras in Nicaragua, Liteky gave the medal back - with a letter to President Ronald Reagan that he laid at the base of the Vietnam memorial in Washington, D.C.

"That was when Ronald Reagan was comparing the contras to the moral equivalent of our Founding Fathers," said Liteky. "By then I'd begun to wake up about what my country was doing to Latin America. I'd studied the history and talked to refugees here in San Francisco.

"Then I had to go down and see for myself, to El Salvador, Nicaragua and Honduras. I was ashamed of my country. And I was ashamed I'd participated in the same thing in Vietnam."

Ironically (or inevitably), Liteky first met some of the casualties of U.S. Latin American policies through the woman who would become his wife.

An Immaculate Heart of Mary nun for 13 years, Judy Balch had left her order for life in the laity in 1978 and moved from her native Los Angeles to San Francisco.

A year of teaching math to poor Latina students in the L.A. barrio had opened her eyes as a nun to the economic and social inequities suffered by many minorities. Social justice seminars, taught by fired-up Jesuits at the University of San Francisco, expanded her horizons and threw her into the company of anti-nuclear weapons activists and people in the "sanctuary movement" for Salvadoran refugees.

In 1980, learning that she was "ready to date," mutual friends picked out a candidate: a tall, Vietnam War hero who was working as a benefits counselor for the Veterans Administration. Like her, he'd changed his mind about how best to serve God; he'd left the priesthood in 1975.

"Right away, I figured she was the one," Charlie recalled last week over a dinner of some of his favorite foods that Judy prepared in their modest Sunnyside neighborhood home.

"I'd had this physical vision in my mind of a tall, slim brunette - and there she was."

Judy had harbored no visions, but she knew at the end of their first date that she wanted to see more of Charlie Liteky:

"I dropped him off near where he was living in the Tenderloin, and I was so bold as to lean over and kiss him goodnight."

It would take more than two years for Judy to say yes to Charlie's entreaties to marry. During that time he took his wounded pride to a cabin in Colorado with the idea of writing a novel, ''But I ended up writing more love letters to her than I did chapters of the book."

Finally, on Oct. 22, 1983, the former nun and former priest were married in Judy's parish church, St. John of God. The bride was 41, the groom 52.

Three years later, Judy learned that being Charlie Liteky's wife would be like no other challenge she'd ever imagined: He told her he was going to Washington with another vet to protest U.S. aid to the contras with a water-only hunger strike on the Capitol steps.

"That decision had a finished-product characteristic to it. I had no impact on it," said Judy. "I do a little better when I have time to reposition myself, when things unfold, like the stages of this arrest and trial."

Said Charlie: "I don't know what I'd have done at that time if she'd said no - I probably would have gone ahead. But she didn't. She objected, but she was very good at listening to what was going on in my soul, and she honored that. She always has."

Honoring the goings-on in Charlie Liteky's soul would test the boundaries of any wife's love and commitment. A math, science and engineering teacher at Canada College in Belmont, Judy has spent long stretches away from Charlie, earning the bulk of the couple's income while he has been at the center of the decade-old campaign to close the School of the Americas.

In addition to his dangerous 47-day fast, she endured Charlie's first trespassing prison sentence in 1990 - six months in the federal pen in Allenwood, Pa.

Now, it's Lompoc for a year.

"Like going to war, going to prison as a protest is not a self-contained experience," said Judy. "I get a year's sentence, too."

It helps that she and Charlie still believe in a Creator whose son commanded his followers to love others without exclusion and to help the poor, enslaved and oppressed.

It helps, too, that Judy has been an astute student of social justice politics. When the annual march on Fort Benning comes around in November, she'll be there without Charlie.'

"The SOA movement has been an important one to both of us," she said. "I often think of those four Maryknoll nuns who were raped and murdered in El Salvador in 1980. I could imagine myself there, people like me being those women.

"I'm also aware that citizens' lobbying is not a sufficient way to change the U.S. government and its policies. The role of nonviolent protest is essential."

But, as both Litekys admit, political activism carries a high price.

"A year is a long time," Judy said, looking across the dining room table at Charlie. "He won't be home for dinner. I won't embrace him. So I am going to have to stretch and hope I'm going to learn what I need to learn while he's in prison."

Already, that stretching - and Barbara Sonneborn's documentary "Regret to Inform" - have led Judy to empathize with and connect spiritually to the actual widows of war.

"Women's way into the suffering of war has traditionally been through men," she said. "Wherever we met them, however we came to love them, we became their widow. In a sense, I'm learning what it is to be Charlie's Vietnam widow."

Perhaps the biggest help of all comes from the fact that Judy Liteky loves her husband with a quiet ferocity that can only come with long years and a shared mission.

"There is a history we can't take out of ourselves anymore. I can't not have known him this long," she said. "Through working with Charlie, I've had an incredible set of experiences, learning what it means for women to become a political voice.

"He's also shown me the importance of the symbol of witness - in prison or in crossing the line at Fort Benning. In a practical, greedy world, I believe it's important to all of us to surrender to such a symbol."

One break the Litekys will get in the coming year: Their 17th wedding anniversary falls on a Sunday. Judy will be permitted to visit Charlie in Lompoc.

"It won't be a consummated anniversary," Charlie joked.

"But I WILL be there," Judy said. "I promise."

(Return) to SOAW-West Main Page