Articles

NICARAGUA- SPEAKING UP

Solidarity in Times of Internet

JILL WINEGARDNER

Solidarity in times of Internet

When the alert went out in the United States

about the persecution of a US nurse in Nicaragua,

thousands of people responded and kept on responding

until the Nicaraguan government was forced to "desist."

The head of that campaign reflects back on

what this case can teach us about

solidarity in the Internet era.

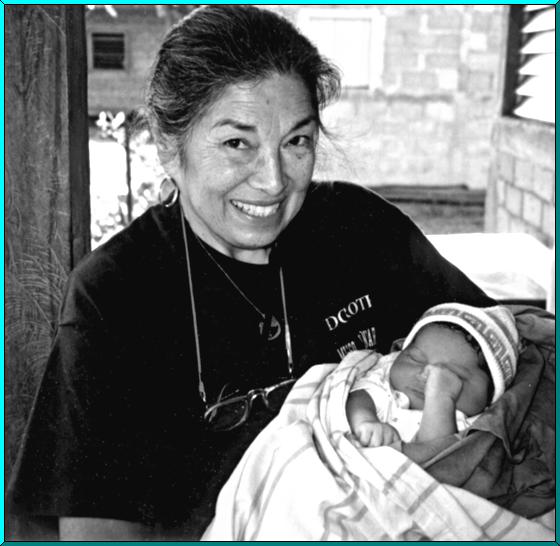

When retired US nurse Dorothy Granada went into hiding late last year upon

learning that the Nicaraguan government planned to deport her on fabricated

allegations of "working against the government," the campaign on her behalf

did not have to start from scratch. Immediately upon receiving the alert, a

support system created years earlier mobilized to demand respect for her

immigration status and her right to due process. It won its first major

battle when Minister of Government José Bosco Marenco publicly announced

that the government was "desisting in its efforts to deport Dorothy

Granada." This vigorous campaign was aided by the fact that we are now in

the age of instantaneous mass communication.

The seeds of support

Dorothy first went to Nicaragua with Witness for Peace in 1985, where she

saw the grave need for women's health clinics in poor rural areas and

decided to work in that field. To gain special training, she went to

California and worked at the Santa Cruz Women's Health Center for two years.

When she returned to Nicaragua in 1989, she was invited to Mulukukú, a

community deep in the impoverished north-central part of Nicaragua. Joining

with local women, she helped found a clinic through a program with the

María Luisa Ortiz Women's Cooperative there. Her friends in Santa Cruz soon

formed "Friends of Dorothy Granada and the Mulukukú Women's Clinic," a

small but dedicated core group that raised funds, organized Dorothy's US

speaking tours and published her newsletters, as well as providing her with

personal support over the years.

I had become friends with Dorothy when I lived in Nicaragua between 1990

and 1992, so when I moved to Santa Cruz County in 1998, I soon joined the

group. By that time it was grappling with the task of managing an entirely

too successful and decentralized project with a large budget and growing

demands. We decided that we needed to set up a non-profit organization and

bring some clarity to the US side of the project's management, which we are

now doing, under the name Women's Empowerment Network (WEN). Our key

community development project will of course be the Women's Center in

Mulukukú together with its urban counterpart, the Consuelo Buitrago Women's

Association in Barrio Walter Ferretty, my old neighborhood in Managua.

Meanwhile, Dorothy began developing ties with groups across the country

that have visited Mulukukú, including a Missouri pastor who even before her

arrival brought work delegations and continues to do so every year, medical

delegations from Indiana and Texas that also come yearly and many other

individuals and groups. To systematize this growing network, Dorothy

compiled a list of "key contacts," which included these delegation leaders,

the local "Friends" and other key clinic supporters, medical people and

groups, church groups, solidarity groups and many individuals, from Texas

Republicans to radical lefties, who simply love Dorothy and respect her

work. This list-which has now grown to several hundred names-proved crucial

in our emergency efforts.

The list put on alert

On Saturday, November 25, my phone rang at about 4 am. It was Noel Montoya,

a Sandinista leader and former mayor in Mulukukú, who was calling for

Dorothy and wanted me to mobilize the list. He told me that President

Alemán had arrived on November 14 to help inaugurate a housing project

sponsored by the Taiwanese government and honor several community leaders,

including Grethel Sequiera, vice-president of the women's cooperative and

Noel's wife. While there, the deputy mayor of a neighboring municipality

told Alemán that the clinic served only Sandinistas; he publicly threatened

to investigate and throw the leaders in jail; Grethel snubbed him by just

thanking the Taiwanese representative and two days later government

officials were in Mulukukú inspecting Dorothy's immigration papers.

Within days, the government closed the cooperative and threatened the

clinic into closing down, a move that the Ministry of Health (MINSA) made

official on December 12. The Nicaraguan Human Rights Center (CENIDH) and

the Civil Coordinator, a superstructure of NGOs and social organizations

created two years ago in response to Hurricane Mitch, were already on the

case, as were Dorothy's lawyers. In the ensuing weeks, the clinic would

also falsely be accused of performing illegal abortions and of treating

members of an anti-government armed group called the Andrés Castro United

Front (FUAC).

My obvious initial reaction was concern for Dorothy's safety and alarm for

the clinic, but I remember also having a clear sense that we in the States

should take our direction from Nicaragua. I knew that national politics are

very complicated and I would never pretend to understand them from afar. So

I got up, turned on my computer, pounded out a description of what had

happened and sent it to the 90% or more of our list that has email, then

called or wrote the rest.

That first "Urgent Action Alert" opened with this paragraph: "Today we

received word from Dorothy Granada in Nicaragua that the government of

Arnoldo Alemán has ordered an investigation of the Women's Clinic in

Mulukukú and of Dorothy. Dorothy asks that you spread the word and mobilize

your groups to send faxes to the US Ambassador in Nicaragua." Ambassador

Garza was soon so swamped with messages that he called in USAID

investigators, who found that the clinic had been doing exemplary work.

We also started contacting Congress members. I got my mom to call Sen. Max

Baucus of Montana, since they are friends, and he ended up being among our

earliest and best congressional supports, together with Rep. Brian Baird of

Washington and Sam Farr, who is our (and Dorothy's) district

representative. By the end, the US Embassy had received hundreds, perhaps

thousands of faxes from Congress members, individuals, church groups and

organizations ranging from classes of schoolchildren to Elders for Survival.

Unwelcome birthday greetings

The next pre-dawn alarm call was from Dorothy herself-at 4:30 am on

December 8, her 70th birthday. She had unexpectedly stayed over in Managua

the previous night and Noel had just radioed her to report that a dozen

armed police and immigration officials had her house in Mulukukú

surrounded. When she spoke by radio to the immigration officials, they said

they just wanted to ask a few questions, but we later learned that they had

reserved a seat for her on a 9 am flight out of Managua…for that same day!

Dorothy's first reaction was to tell them she was on her way back to

Mulukukú. As she explained to me with her typically automatic concern for

her patients, "I have a group of sick women here I have to take home." But

she was quickly persuaded that she needed to go into hiding. From then on,

she and I only spoke in brief, careful calls. Someone else kept me up to

date on what we needed to do.

Moving into emergency mode

Once it became clear that this would be an extended campaign, we decided to

hire Gerry Condon, a long-time anti-war and solidarity activist who led

several veterans' delegations to Nicaragua in the eighties, to work full

time on it. We met regularly with WEN, whose members took on tasks such as

writing articles for publications or making press contacts, but with the

campaign headquartered in my little home office, Gerry and I did the bulk

of the work. Luckily, I had experience organizing by computer (we put

together the 1996 international women's election delegation to Nicaragua

almost entirely that way since it had observers from 18 countries). Gerry

has special talents in networking, writing and working with the press, and

had anchored several protracted emergency response efforts while a national

coordinator of Pastors for Peace.

We essentially went into Emergency Mode from Day 1. Each morning we would

race for the computer chair and log on to see what the day had

brought-typically dozens of messages, requests for articles, suggestions

for other actions or contacts, notes of support, etc. Then we would go into

Internet to get fresh information from the Nicaraguan newspapers La Prensa

and El Nuevo Diario for our Urgent Action Alerts.

The initial strategy to bombard Ambassador Garza with requests for help

came from Dorothy and her advisers in Nicaragua, and his embassy remained

the prime focus throughout the campaign. Although we encouraged people to

be positive in their faxes and emails, the embassy was never allowed to

forget that so many US citizens were counting on it to defend Dorothy's

personal safety and her legal and human rights. On advice from Dr. Vilma

Núńez of CENIDH, Ana Quirós of the Civil Coordinator and others in

Nicaragua, we added various other key players. These included President

Alemán, his health and government ministers, his ambassador to the US, Dr.

Benjamín Pérez of Nicaragua's Human Rights Commission-who ended up writing

a very critical position paper on the government's actions-and key people

in the State Department. More often than not, there were multiple targets.

A multi-tiered campaign

Even with this emergency focus to protect Dorothy's rights and do whatever

possible to prevent her deportation, our intent all along was to make the

campaign multi-leveled. Our second goal-also urgent-was to protect the

clinic and get it re-opened. But we also wanted to raise awareness and

educate North Americans about the situation in Nicaragua in a larger

sense-particularly but not only the plight of NGOs and women in general-and

through this information and consciousness-raising effort help renew

interest in Nicaragua solidarity.

This last point grew out of the fact that we began receiving calls and

emails from literally dozens of people who could not fathom why the

Nicaraguan government would attack such a positive, life-giving project as

the women's clinic. At the same time, several Nicaraguan friends began to

emphasize the importance of describing the attacks on other NGOs as part of

our focus. Several US groups with projects in Nicaragua that had also told

us they needed to keep a low profile to avoid drawing Alemán's attention

helped us appreciate the climate of intimidation he was imposing on the

NGOs even more.

So I called down to a friend in Nicaragua to see who could put together a

good analysis, because I couldn't make sense of it to a US audience. Within

twenty minutes, Ana Quirós, director of the Civil Coordinator, was on the

phone. As head of a coalition of over three hundred independent NGOs and

grassroots social organizations-and as someone else the government tried to

deport but failed because she has Nicaraguan citizenship-she probably knows

more about these issues than anyone. She gave me a half-hour talk on the

political context of this case as I took frantic notes. I then wrote it all

up, added a few bits and sent it out. It was extremely helpful for

explaining Dorothy's plight and provided a solid foundation for broadening

and deepening the campaign's focus.

Networking…

The small Friends of Dorothy group was never good at networking with local

or national solidarity groups, largely because it has a huge amount of work

just to support the clinic. Ironically, Gerry used to say, "You know, this

is a great project, but nobody even knows about you. You should be more

political." Now, that has all changed.

Gerry did most of the networking, particularly with groups historically

linked to Nicaragua. He contacted the Nicaragua Network, Pastors for Peace,

Witness for Peace, Quest for Peace, the Wisconsin Coordinating Council on

Nicaragua, MADRE, the Coalition for Nicaragua, Elders for Survival and the

Marin Interfaith Task Force. We added all these and other groups to our

list so that they received the updates and press releases.

The Nicaragua Network's support has been particularly outstanding: they

regularly posted our updates to their members, included us in their Hotline

and featured several stories about Dorothy and/or the larger context in

their newsletters, including the NGO analysis. But virtually every group

did something, whether printing an article in their newsletter or sending

faxes at the critical early stages of the campaign. Many local solidarity

groups and formal or informal networks also rebroadcast our alerts to their

own contacts, thus expanding our overall outreach considerably.

Our campaign is even known internationally. Early on, someone gave us the

contact for Amnesty International, which eventually put out a worldwide

action alert for Dorothy that generated faxes and letters from many

countries to both the Nicaraguan government and the newspapers there. Dr.

Pérez of the Human Rights Commission said his office received an average of

250 emails a day from the United States, Europe, even New Zealand.

We had some other international contacts, such as the Nicaragua Solidarity

Campaign in Britain, though not as many as I would have liked, and I later

learned more of the efforts other countries made. For example, I understand

that the Swiss government was actively working behind the scenes on behalf

of Ayuda Obrera Suisa, an NGO from that country that the Nicaraguan

government closed at the same time for supporting the Mulukukú women's

cooperative. Immigration even sent officials there to look for the NGO's

director, with the apparent intention of deporting her too. But this

capricious move backfired on the government, as did so many others in this

case: the Swiss had hired a Nicaraguan woman to direct it.

…responding to moments…

We generally had one major new goal per week, and whenever possible altered

the focus of our outreach in response to what was happening in Nicaragua.

For example, right when we were helping organize a letter from several

important US ecumenical groups to appear as a paid ad in Nicaragua's

newspapers, we heard that criticism of US interventionism was being voiced

in Nicaragua. Though it was related to a different case, we decided to take

the time to broaden the sponsors of the ecumenical letter. Church groups

from Honduras and El Salvador and both CEPAD and CIEETS from Nicaragua

joined on, which was all to the good.

Later, when it seemed that Ministers of Government Marenco was hardening

his position, we decided we needed another letter to go in the papers, this

time from Congress. By then, Representatives Sam Farr and Cynthia McKinney

had already circulated a Dear Colleague letter in Congress and our network

members had been calling their respective representatives, so the case was

known. I called Farr's aide to ask if they would be willing to circulate

another letter, this time to be signed and sent to the government of

Nicaragua. She responded that she had just been writing us with a similar

idea.

At that time, we were awaiting an important decision by the Nicaraguan

Appeals Court on the legality of the deportation order against Dorothy. I

intuited that the congressional letter should be sent right away, to

fortify the court's independence and add weight to the government's

obligation to respect the positive decision we were expecting. So we set a

deadline of a day and a half for collecting signatures. With the Washington

Office on Latin America (WOLA) also calling congressional offices, we had

half a dozen signatures within a few hours, which Farr's aide thought was a

good response. Much to our surprise, particularly given how strong the

letter was, we ended up with 32 signatures, including even conservative

Republican Dan Burton of Indiana.

…and making it easy

We also learned that if you want someone to take an action in writing,

write a draft for them. This not only prompts them to move on it right away

but also makes it more likely that the letter will approximate what you

want. On the other hand, we decided early on not to write form letters for

people because we saw that people speaking in their own voices could be

more eloquent than we ever could be.

Gerry drafted the congressional letter, then I toned it down a little-our

standard division of labor. We assumed the signers would tone it down a lot

more but, again to our surprise, the only change they made was to replace

our last line, which was something like "We wish you a happy and prosperous

year," with "We look forward to your prompt reply."

Maybe the draft went through because its most powerful statements came from

the US government's own stated goals for its foreign aid to Nicaragua,

which Gerry found on the AID page of the US Embassy's website on

Nicaragua-another Internet benefit. It explicitly supported the work of

clinics very much like Dorothy's, including family planning, and called for

strengthening democratic institutions such as the legal system and the

office of the Human Rights Ombudsman. Great ammo from the horse's mouth!

Congress in the post-Cold War context?

In early January, I called Sen. Bingamon's office in New Mexico. When I

asked the person who answered if they knew of Dorothy's case he said, "Are

you kidding? It's the buzz of the Congress."

I can't compare our experience of involving Congress with efforts of

earlier periods because I don't have them, but it actually seemed fairly

easy. We had repeated good conversations and interactions with the various

congressional offices, which for the most part got involved. The signers of

the congressional letter were also very interested in the response after it

had appeared in the Nicaraguan papers.

Important points in this work included connecting Dorothy to the state of

the legislator we were calling (luckily she lived in many states in her

life!) and stressing the human rights aspect of the case. Another was to

identify a congressional aide who would take on the project and stay in

touch. Particularly from our experience with Rep. Farr's office, we learned

that it is just as important to have a competent aide able to make the

effort a priority as to have a willing Congressperson.

Constituents' personal calls seemed most important. For example, Max Baucus

does not deal with international affairs to my knowledge and Dorothy is

not from Montana, but he responded to a personal call. And because he is a

senior senator, we could then tell other Congress members that "Sen. Baucus

has made calls, so we hope you will too."

Finding strong-point people was also important. Rep. Farr, for example, is

a liberal Democrat who gets a lot of encouragement from progressive groups

here, including the Coalition for Nicaragua.

Media on board

The Nicaraguan media played a mammoth role in this case. All except those

sponsored by the government were supportive and involved right from the

beginning. There wasn't a single negative story in the papers, TV or radio,

and they kept the case in view the whole time, generating huge public

sympathy.

In the United States, the AP wire service and The Miami Herald ran a few

stories at key moments-including the victory-which were picked up quite

widely; we heard from people in Alabama, Virginia, Colorado, Arizona and

other states who saw them in their local papers. There were also several

national radio segments, including a program called "The World," which is

co-sponsored by the BBC and a Boston station, and a great report on

National Public Radio in mid-January.

Gerry's experience with previous urgent action campaigns taught him that

the large corporate media were likely to ignore this story, no matter what

we did, particularly since post-contra war Nicaragua is rarely covered. So

we concentrated our limited resources on the action alerts, sent out

regular press updates, and cultivated those media that showed any interest.

One can only wonder how much money and effort it would have taken to get an

article in The New York Times, The Washington Post or any of the major

television networks.

Contributing to Nicaraguan unity in action

This case appears to have united Nicaraguan organizations that have not

worked together for some time. For example, the famous 10,000-person march

in Managua protesting the government's treatment of Dorothy and the clinic

was a coalition of labor, different branches of the women's movement, human

rights groups, the peasant and cooperative movements and NGOs coming

together for a common purpose. A women's leader from FETSALUD, the public

health workers' union, attributed the success of its own march of 3-4,000

people (to protest the health minister's failure to include significant

legislated salary increases in their paychecks) to the energy generated by

this march. She reported that people from poor neighborhoods joined them

because they saw hope for the first time in ages. The papers then and still

today are full of stories about patients clamoring for their health rights,

and we think this case played some role in promoting these demands.

People in Nicaragua who rallied around the case came from across the

political spectrum. On one live TV interview with Dorothy that I saw just

after the government withdrew its attempt to deport her, people were

unanimously supportive of her position. One caller admitted that "I'm a

Liberal but I am ashamed of my government."

So many people from Mulukukú wanted to go to the march in Managua that

there wasn't enough transport and I was told that Sandinistas stayed home

so Liberals could go. Then at the event in Mulukukú to welcome Dorothy home

after her two months "underground," the speakers included an ex-contra from

another community, evangelical Liberals, representatives from the Union of

Farmers and Ranchers and from the women's movement in Matagalpa and Estelí,

along with local people and us internationalists. The most touching speaker

was a woman with a small boy in her arms who said that the boy's twin

brother had died of asthma shortly before because the clinic was not open.

The larger framework of success

Obviously, the Internet and its instant worldwide communication was key,

but it is simply a tool that has come of age and made our work infinitely

more efficient. In other words, it may explain how people got mobilized,

but not why.

I think this campaign was so powerful and successful for several reasons.

First is that many of the people who participated were not strangers to

Nicaragua; they came to know it while opposing the US-sponsored contra war

of the 1980s. And unlike most of those who opposed the US war in Southeast

Asia in the sixties and seventies, many of these people actually visited

Nicaragua and still feel a personal connection.

Next is the context: in this unipolar, increasingly globalized world, with

the cold-war paranoia and distortions largely behind us, awareness of and

concern about the plight of the South has grown exponentially in the North.

This has created movements such as 50 Years Is Enough, Jubilee 2000 and the

opposition to the World Trade Organization. This in turn has generated

genuinely global communication networks of people with shared, overlapping

and inter-linked values and concerns ranging from environmental issues, to

poverty and development issues, to empowerment for the historically

oppressed, to basic, underlying human rights demands, and from there

sometimes to a questioning of what democracy even means if all these other

issues are not truly addressed.

In this context, it would be hard to find another case as clear-cut and

symbolic as this one. Virtually the only good work in Nicaragua today is

being done by groups that are not governmental, yet the government went

after one of the few remaining solidarity projects in a remote area with

absolutely no other viable health resources. Is it any wonder that it made

no sense to people in the States? Furthermore, the attack on women

resounded strongly in the country and abroad, since this clinic aims to

provide women with health care and teach them their health rights and human

rights.

The personal is political

Last but certainly not least is the person the Alemán government quite

mistakenly chose to go after. Very important factors made Dorothy Virginia

Granada possibly the one person in all of Nicaragua most likely to have

generated this amount of internal and international support:

* The sheer force of her personality. Her spirit and dedication especially

motivated those in the United States who had met her personally. We even

know of people who heard the radio stories and remembered her from the past

or simply recall having heard her on one of her speaking tours.

* Her clear vision and articulation of her philosophy of Christian

commitment to the poor. People ask if she was coached on what to say in the

always-compelling and captivating media interviews. Never. Dorothy spoke

from a lifetime of nonviolence training and of faith and personal focus

that allows her responses to flow cohesively and cogently.

* Her history-this campaign was joined not only by people who know her work

now in Nicaragua, but also by those who knew of her actions for nonviolence

years ago in the US.

* Her 10 years spent creating a climate of inclusiveness and reconciliation

in the highly conflictive and polarized Mulukukú area.

* Her ability to cross many cultures and political borders. She is equally

at home and genuine giving fiery political talks in the US, charming the

populace on Nicaraguan TV, directing her rural health clinic and praying

with peasant mothers as she tries to save their babies.

* The varied and widespread US support base for the Mulukukú work. Dorothy

has prioritized delegations that want to forge a relationship with the work

over those that want to come down for a one-time visit, so most people

working on this campaign had a very personal connection to Mulukukú. Also,

by including health workers, religious groups, solidarity activists,

feminists and miscellaneous supporters, the base for that project has more

variety than most.

* The fact that the case seemed to touch the heart of Nicaraguans' fears

and concerns about their basic health rights, women's rights, and human

rights gave them a champion they felt they could trust in these times of

powerlessness and political cynicism.

Renewed US interest in Nicaragua?

After suffering many disappointments along with the people of Nicaragua,

such a collective victory was a shot in the arm for everybody who

participated in the campaign in the United States. Many people have said to

us, "It feels so good to win one for a change! We really needed that."

We hope we've contributed to rekindling consciousness about Nicaragua in

the US. Certainly, the response from our network has been overwhelming and

intense, and many people commented that the campaign had renewed their

interest in Nicaragua issues. We think there's a real opportunity for

well-designed initiatives right now to raise the level of solidarity work

in the US. We hope to seize this opportunity by continuing to strategize

about ways to keep the focus on Nicaragua as we shift from Dorothy's

specific case to reports on the government's abuses and corruption and to

support for NGOs and for women's issues.

We also need to be aware, however, that we have not yet won all the

battles. For one, the Ministry of Health was less than attentive to

Dorothy's proposals to meet what many of us feel are its punitive

conditions for reopening the Mulukukú health clinic. For another, the

government filed its claim against Dorothy with the Supreme Court, which is

due to render a decision in the coming weeks. We have mobilized our network

yet again to encourage both MINSA and the Supreme Court to do the right

thing. Members of Congress Farr and McKinney have also sent a strong letter

to the Supreme Court to let them know the United States is still very

interested in this case.

As for Nicaragua itself, I hope the bigger outcome of the case is that

people will have become aware of this government's attitude toward the

poor, toward women and toward NGOs. I hope that somehow it will spark the

best of reconciliation and mutual respect and that people will hear the

message Dorothy gives her patients: know your rights, demand them and vote

for the party most likely to respect them.

Jill Winegardner is a neuropsychologist who taught neuropsychology during her two years in Nicaragua and has organized a number of delegations to the country.

Check List of a Successful Email Campaign

BY GERRY CONDON

* In the two months of the campaign before the first victory, we sent

nearly four dozen action alerts and other messages to Dorothy's list and

everybody else we could think of. Since we also sent all our press releases

to the entire network, people received communications a couple of times a

week. With those on her list constantly giving us new contacts, forwarding

the messages to their address lists and mobilizing their local churches and

solidarity groups, the campaign spread like wild fire.

*

Our email list was made up of those who were truly interested in this

campaign; we did not bombard unsuspecting people who just happened to be on

some progressive list. We also constantly gave positive feedback about the

daily or weekly actions we were urging people to do; for example when we

got word that the Embassy was getting so many faxes it was bundling them up

and sending them over to Nicaragua's Foreign Ministry.

*

We set up five recipient categories: key contacts, organizations,

government (congressional offices), media and general supporters. Mainly,

we sent the updates and press releases to all categories, but could target

and prioritize as needed, and even vary the headings according to the

recipient group.

*

Early on, we organized our alerts into four sections: Update, Analysis,

Suggested Actions and Contacts. Those in a hurry, who just wanted to know

the action focus for that week, could scroll straight down to Actions, then

to Contacts for the relevant fax and email numbers.

*

We were religious about providing timely, accurate and complete updates,

always supported by a concise analysis, and did our best to avoid rhetoric

and just give people the facts. On the advice of those experienced in email

campaigns, we gave them a consistent and thus familiar appearance, always

heading them the same way and, within the limitations of basic email text,

making the messages attractive.

* The Internet was pivotal to everything we did, from the original email to

our Key Contact group, to all the press releases and action alerts we sent,

to the amazing amount of personal communication we had with individuals in

our network. It allowed us to access the Nicaraguan newspapers, send

detailed reports on a regular basis, have a good handle on the nature and

level of responses and be immediate in our actions.

* Email does ultimately allow for a great deal of democratic input. When

people suggested support actions to us, we often incorporated them into the

campaign, or in some cases they became the major focus for that week, for

example getting the ecumenical letter to President Alemán also printed as

an ad in Nicaragua's daily papers.

* Not all was electronic; we had a huge grassroots response from

individuals in which various people asked for and were given "the ball to

run with." One group met with the Nicaraguan Consul in San Francisco;

another organized the ecumenical letter and other church-related responses;

and various individuals and groups played other important

roles at key moments. They all showed so much respect and appreciation for

the centralized coordination that we never had to deal with people doing

something inappropriate or at cross purposes with the priorities. Perhaps

part of the reason for that is that we wanted the updates to have a

personal feeling, as well as being well written and "professional." People

knew that they were coming from "Jill and Gerry," and that they could call

and talk to us, thank us, or make any kind of suggestion and they would be

well received.

* Then there was the fantastic website-www.peacehost.net/Dorothy-that

Daniel Zwickel, a Berkeley peace activist and musician, volunteered to set

up and manage for the campaign, so we could refer people to it for the

latest detailed information and even photos. Occasionally we just sent out

a short message saying, check out a certain article and/or picture on our

website. Where possible, we provided working links to email addresses and

the site, making it possible for people to click and be on their way.

An email campaign without a website would have been rather one-dimensional.

It provides a permanent presence that can be accessed anytime from anywhere

and contains all the information an individual could want. We got calls

from reporters who were already on the website and therefore already

interested and informed. Some people who for whatever reasons could not

receive email, sometimes could access the website. It was also valuable for

people who did not want to be on an email list.

* Speaking of that, one initial mistake we quickly corrected was that the

first few updates had all email addresses visible for all to see. This is

poor security and also invites mischief. In fact, our key contacts all

received one contrary message from a conservative supporter of Dorothy who

was angry that we had described the contra war as being "US-backed" in a

fundraising letter. We learned it was a good idea to keep all addressees in

the "bcc" (blind copy) section of the address area.

* Finally, of course, there are those without access to email. A few people

called and asked us to mail updates to them. And, no doubt, some people

were left out altogether because they didn't have email access or we didn't

have their address. But the Internet clearly far surpasses other means of

communication for efficient use of scarce resources. What is interesting is

how few people, at least in the US, are left out. According to recent

polls, 56% of people in the States now have access to the Internet, with

much higher numbers for younger people and much lower for those over 65. To

make sure the older group is included, perhaps a parallel telephone network

should be established.