Nonviolent Soldier of Islam

Badshah Khan, A Man to Match His Mountains

by Eknath Easwaran

[Book ordering information below]

Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan (1890-1988), a Pathan (or Pushtun) of Afghanistan, a devout Muslim, raised the first nonviolent army in history to free his people from British imperial rule. He persuaded 100,000 of his countrymen to lay down the guns they had made themselves and vow to fight nonviolently. This book tells the dramatic life-story of this heroic and too-little-known Muslim leader. It gives at the same time a glimpse of the Pushtuns, their society, 100 years of their recent history, and describes the rugged terrain in which they live.Khan’s profound belief in the truth and effectiveness of nonviolence came from the depths of personal experience of his Muslim faith. His life testifies to the reality that nonviolence and Islam are perfectly compatible.

Nonviolent Soldier of Islam tells Khan's life-story through narrative, 58 photos and Khan’s own words.

Excerpt from Nonviolent Soldier of IslamFrom Chapter Nine of

Nonviolent Soldier of Islam, Badshah Khan

by Eknath Easwaran

They called themselves Khudai Khidmatgars, “Servants of God.” Their motto was freedom, their aim, service. Since God himself needed no service, they would serve his people.

The Khudai Khidmatgars, under the leadership of Abdul Ghaffar Khan, became history’s first professional nonviolent army – and its most improbable. Any Pathan could join, provided he took the army’s oath:

I am a Khudai Khidmatgar; and as God needs no service, but serving his creation is serving him, I promise to serve humanity in the name of God.

I promise to refrain from violence and from taking revenge.

I promise to forgive those who oppress me or treat me with cruelty.

I promise to refrain from taking part in feuds and quarrels and from creating enmity.

I promise to treat every Pathan as my brother and friend.

I promise to refrain from antisocial customs and practices.

I promise to live a simple life, to practice virtue and to refrain from evil.

I promise to practice good manners and good behavior and not to lead a life of idleness. I promise to devote at least two hours a day to social work.

For a Pathan, an oath is not a small matter. He does not enter into a vow easily because once given, a Pathan’s word cannot be broken. Even his enemy can count on him to keep his word at the risk of his own life. Nonviolence was the heart of the oath and of the organization. It was directed not only against the violence of British rule but against the pervasive violence of Pathan life. With it they could win their freedom and much more: prosperity, dignity, self-respect.

Khan drew his first recruits from the young men who had graduated from his schools. They flocked to him. Trained and uniformed, they snapped in behind their officers and filed out into the villages to seek recruits. They began by wearing a simple white overshirt, but the white was soon dirtied. A couple of men had their shirts dyed at the local tannery, and the brick-red color proved a breakthrough. It did not dirty easily, the dye was cheap, and – best of luck – it had style. Villagers dropped their plows to see who these glowing figures were.

Recruits did not come easily, but Khan and his eager young volunteers persisted. Within a few months they had five hundred recruits – not enough for a Raj-shattering holy war, but a beginning. Volunteers who took the oath formed platoons with commanding officers and learned basic army discipline – everything that did not require the use of arms. They had drills, badges, a tricolor flag, the entire military hierarchy of rank – and a bagpipe corps.

Khan set up a network of committees called jirgahs, named and modeled after the traditional tribal councils that had maintained Pathan law for centuries. Villages were grouped into larger groups, responsible to district-wide committees. The Provincial Jirgah was the ultimate authority. Since all the committees were filled by elected officers, the Provincial Jirgah became a kind of unofficial parliament of Pathans.

Officers in the ranks were not elected, since Khan wanted to avoid infighting. He appointed a salar-e-azam or commander-in-chief, who in turn appointed officers to serve under him. The army was completely voluntary; even the officers gave their services free. Women were recruited too, and played an important role in the struggles to come.

Volunteers went to the villages and opened schools, helped on work projects, and maintained order at public gatherings. From time to time they drilled in work camps and took long military-style marches into the hills. As they marched, they sang:

We are the army of God,

By death or wealth unmoved.

We march, our leader and we,

Ready to die.

We serve and we love

Our people and our cause.

Freedom is our goal,

Our lives the price we pay.Watching the narrow columns threading a curving mountain pass, one could easily imagine that some angry mullah was unleashing another holy war against the foreigners. But these Pathans, who for years had carried rifles and tucked small armories of revolvers and knives inside their waistbands, now carried only a stick for walking. They armed themselves only with their discipline, their faith, and their native mettle.

“The Holy Prophet Mohammed came into this world and taught us ‘That man is a Muslim who never hurts anyone by word or deed, but who works for the benefit and happiness of God's creatures.’ Belief in God is to love one's fellow men.” – Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan

“There is nothing surprising in a Muslim or a Pathan like me subscribing to the creed of nonviolence. It is not a new creed. It was followed fourteen hundred years ago by the Prophet all the time he was in Mecca.” – Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan

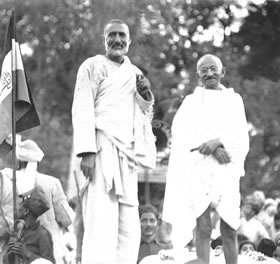

Khan and Mahatma Gandhi worked closely together with great mutual respect using and shaping the practical tool of nonviolence to gain independence for their people. They both believed that the uplift of their people was essential preparation for independence. Khan opened schools, brought the women out of the home into roles in society, and included a vow taken by his nonviolent soldiers to do at least two hours a day of social work.

“To me nonviolence has come to represent a panacea for all the evils that surround my people. Therefore I am devoting all my energies toward the establishment of a society that would be based on its principles of truth and peace.” – Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan

“Today’s world is traveling in some strange direction. You see that the world is going toward destruction and violence. And the specialty of violence is to create hatred among people and to create fear. I am a believer in nonviolence and I say that no peace or tranquility will descend upon the people of the world until nonviolence is practiced, because nonviolence is love and it stirs courage in people.” – Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan to an interviewer in 1985

From the Introduction:

“It my inmost conviction,” Badshah Khan said, “that Islam is amal, yakeen, muhabat” – selfless service, faith, and love.” Yakeen, faith, is an unwavering belief in the spiritual laws that underlie all life, and in the nobility of human nature – in particular, in the ability of every human being to respond to spiritual laws. It implies a profound belief in the power of muhabat, love, to transform human affairs, as Badshah Khan, like Gandhi, demonstrated with his life. This is not the sentimental notion of love portrayed in films. It a spiritual force which, when drawn upon systematically, can root out exploitation and transform anger into love in action. Badshah Khan based his life and work on this profound principle, raising an army of courageous men and women who translated it into action. Were his example better known, the world might come to recognize that the highest religious values of Islam are deeply compatible with a nonviolence that has the power to resolve conflicts even against heavy odds.

The Shahur Pass in Waziristan

Badshah Khan and Mahatma Gandhi during Gandhi's tour of the Frontier in 1937.

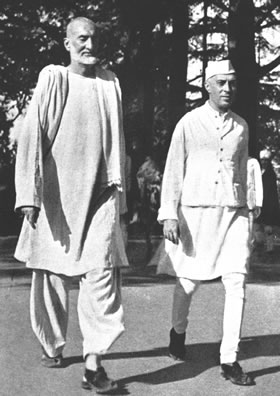

Badshah Khan and Jawaharlal Nehru, 1946

Badshah Khan with Mathama Gandhi bringing people together in Bihar during the riots of 1947

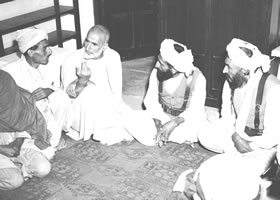

Badshah Khan working with a tribal council in the 1950s

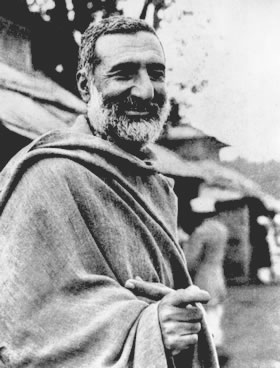

Badshah Khan, shown here at age 95 in 1985, continued to campaign for human rights in his last years

Praise for Nonviolent Soldier of Islam:

“Eknath Easwaran’s great achievement is telling an international audience about an Islamic practitioner of pacifism at a moment when few in the West understand its effectiveness and fewer still associate it with anything Islamic.” – The Washington Post

“A vivid portrait of a too-little known associate of Gandhi, Abdul Ghaffar Khan, a charismatic pacifist Muslim who led the Pathans of India and Pakistan in a nonviolent resistance to British rule.” – Booklist

“By his example, [Khan] asks what we ourselves, as individuals made from the same stuff as he, are doing to shape history.” – The New Yorker

“He was a Muslim voice for tolerance. He was revered by Gandhi, who viewed Khan and his Pathan followers as an illustration of the courage it takes to live a nonviolent life. This book opened me to a perception that Islam can be in harmony with nonviolence.” – Friends Journal

“Few are aware of the nonviolent tradition in Islam. Fewer still know the story of its greatest modern exemplar, Abdul Ghaffar Khan, better known as Badshah Khan. Easwaran's excellent biography deserves the widest possible reading.” – Fellowship

“In these days when one tends to associate the Islamic world with violence, it is refreshing to read the life of a great nonviolent Muslim. Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the ‘Frontier Gandhi’ as he came to be known.” – The Friend

You may order this book (I did!) by clicking on the box below:

© 1997–2002 by The Blue Mountain Center of Meditation*

*[For our Fair Use of Copyrighted material Notice, please click on the ©.]